The quiet Cork city street that was once a bustling trade centre

Today a quiet residential street, Blarney Street was once a hive of trade activity.

Yes, Blarney Street may well be the longest street in Ireland. However, it looks like a tie for the position with Main Street, Cookstown, Co. Tyrone, which claims to be 1.25 miles.

On May 1 last year, on my trusty bike and with GPS watch on wrist, I measured an even mile from Shandon Street to Strawberry Hill (where the city boundary long stood) and a further .24 brought me through Pokertown to the junction with Shanakiel.

But, if I nudged on to Calvary, I would have clocked 1.25, making Blarney Street and Cookstown even at 1¼ miles, or 2km. Cookstown, though, is notably broad and flat, and in 1985 hosted “a right Cookstown sizzler” with a straight mile road-running race. A similar event on Blarney Street would be more akin to hill-running.

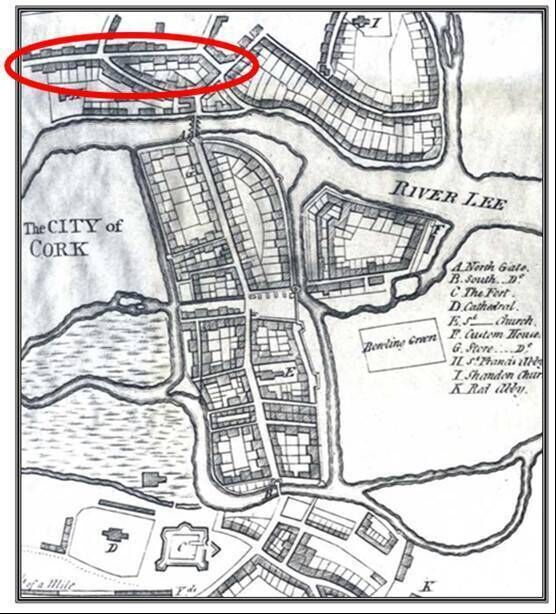

But it has only been “Blarney Street” since 1865. For centuries before that it was known as “Blarney-lane”, and further back again, on Hardiman’s map of Cork from 1602, it appears as the “Highway to Muskerry”. The change from ‘lane’ to ‘street’ was made at a meeting of the city’s “Improvement Committee” when Messrs. Lacy, Harper and Murphy complained they were finding it hard to let houses on it and requested a name change. ‘Lane’ had become synonymous with old, narrow and tending to dilapidated by then. An unsuccessful proposal was “North Castle Street”. Another matter arising at that meeting, incidentally, was the nuisance caused by bathing in the Lee on Sunday mornings opposite St. Mary’s Church, Pope’s Quay. Too close a coming together of the profane and the sacred perhaps.

A man by the name of Kidney, born some years later again, became a market gardener and died in 1799 at the remarkable age of 120. This would mean he was born in 1679. He worked close to the time he died, saying idleness shortens life. Regardless of whether he was quite 120, Mr Kidney “ed Blarney Lane to be forest connected with Dunscombe’s Wood”. This conjures up a very different landscape to today with woods stretching from upper Blarney Street to Clogheen and Mount Desert where the Dunscombe family resided.

The contractor for the 56 miles of work was John Murphy of Castleisland and it came to be known as the ‘Butter Road’, and later, the ‘Old Kerry Road’. It terminated with Blarney Street and long sections were said to be “as straight as the barrel of a gun”.

In 1874, there were mattress-making and woollen factories on the street, while Sullivan Feather Merchants and Hegarty Tanning (not sunbeds!) made it into the 20th century.

In the heyday of the Apostle of Temperance, Fr. Theobald Mathew, Blarney Street had two temperance centres, one at either end of the street and both represented at the great annual march of 1842.

Even then, Blarney Street retained primacy until around 2006 when the junction between the two at Calvary was relined and the priority changed.